- Home

- Linda Byler

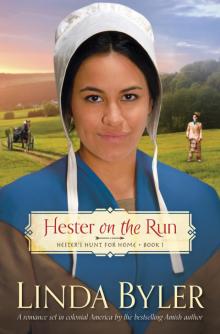

Hester on the Run Page 3

Hester on the Run Read online

Page 3

She would write to them of her precious child, and she would receive a letter from her mother months later. She would be in favor of the Indian child, this beautiful baby who would grow with the Lenape nature of wisdom and faschtendich (common sense) ways.

Kate had no fear of the Native Americans. She often felt pity for them, without speaking of it to Hans. Deep in her soul, she found the arrogance of the Amish settlers disturbing. They were here first, these forest dwellers, their minds a wellspring of knowledge about so many things, especially the ways of survival. When winter and its bitter allies—wind, snow, and cold—threatened their existence, they survived in wigwams covered with bark, and they survived well. Their knowledge was beyond measure. They valued the land, worshiping the Great Spirit. Who was to say they were heathen? Kate didn’t believe they were. The marauding, the murders, and massacres were the only way they knew to protect and keep the land they felt was rightfully their own.

When she felt a tap on her shoulder, she looked up into her young friend Anna Troyer’s smiling face. “Your baby is awake,” she whispered, then sat down smoothly, a smirk of accomplishment on her face. She had been the one to tell Hans sei (Hans’s wife), Kate, that the little Indian baby was awake.

Quickly, Kate left the barn, hurried around the side of it, down the grassy slope to the house, where she found Hester cooing and smiling in Enos Buehler’s wife, Salome’s, arms. “What a pretty child! It takes my breath away,” she said, lifting her face to smile sweetly at Kate.

“She is, isn’t she? We’re guessing she’s Lenape.”

“Oh, I would say so. She looks like them. Her rounded, high cheekbones, the wide, flat eyes. You are surely blessed.”

Eagerly, Kate searched Salome’s eyes, for truth, for honesty.

“Do you … Are you one of those … Do you think it’s all right that we have her?” she stammered, uneasily.

“Why, of course. Kate, you couldn’t let the dear child perish. Don’t you think an Indian girl that was in trouble likely hid the baby for you to find? Who knows? They might be harsh in their punishment of loose girls, so, of course, what else could you do? Surely you believe she’s a gift of God.”

“We do. We do,” Kate said, nodding her head. “But …”

“What?” Salome asked.

“My motherin-law.”

“I heard.”

Salome clucked her tongue, shook her head, said she wished her much gaduld (patience). Kate nodded, but her lower lip was caught in her teeth, her eyes bright with unshed tears.

“Did you sew the dress?”

“Oh yes. It was a work of love. Every stitch was a joy. You can’t imagine how it really is, after nine years.”

Salome laid a kind hand on Kate’s shoulder, gave it a squeeze, and went back to the service, leaving her alone with Hester. She marveled again at her perfect features, the little rosebud mouth, which opened into a smile that melted her heart every time.

Now she would have to grapple with the suspicion of men, or women, and what they thought of her. Of them. Of her and Hans and their decision to keep this little lost Indian baby and raise her in the Amish church. Mostly, they’d been supportive, but still. She’d have to wander among her people with the feelers of a cockroach, waving ahead, searching, checking attitudes, always fearful of a slam, a put-down, a glance of disapproval. Or would she?

Perhaps all she needed to do was hold her head high and be assured, proud of what they had done. So often that was hard to do, the lessons of humility, lack of pride, fear of authority, so skillfully imbedded in her soul, the teachings of the ministers a much-needed discipline. They were necessary, she knew. It was why the Amish stayed free of the worldly ways of excess and pride.

Just sometimes, she wanted to be free of the cross that was hers to bear, the fence that proved to be a two-edged sword. Safety and security, love, a feeling of community; on the other side, the indecision, fear of doing wrong, lack of backbone. Were these ways a safety or a handicap?

At home in front of a crackling fire, Hans lay on the bearskin rug and pulled her down beside him. He apologized for his impatience when Hester cried on the way to church. He stroked her face with his rough hands. He bent to place his lips tenderly on hers and told her he loved her with all his heart.

She returned his love, and far into the night they talked of her fears, her doubts, of Hester being Native American, of his mother’s disapproval. She told him of her lack of resolve, withering under his mother’s stern words.

He explained to her, then, about his mother. She had not been like other mothers, those of his friends. She was harsh. She punished him with a branch from a willow tree that sang through the air before it sliced into the tender flesh of his bare legs.

He rolled onto his back, his hands crossed on his chest. As he spoke, his voice quivered with the intensity of memories that he had not been able to successfully bury. They were pushed back, perhaps, but still alive, as he spoke of the iron hand his mother wielded over him, and still did.

Kate nodded, loving her husband with a new understanding. This, then, was why he loved Hester with such limitless feelings. He wanted a much better life for Hester than he had had, growing up beneath the stern rebuke of a woman who wasted no time in vain glorying her children.

When the baby woke to be fed, they bent their heads together, a beautiful silhouette. In the background, a warm, crackling fire, the picture of perfection, a small family whose foundation was communication, love, and trust.

Hester wasted no time. She drank her milk, burped, and returned to the deep sleep of an infant. Her day had been strenuous, traveling to church with her parents for the first time. Kate tucked her in, kissed her cheek, and said a little German children’s prayer, asking God to watch over her precious baby daughter.

They slept in front of the fire that night, and long after Hans was asleep, Kate lay on her stomach, staring into the red coals on the hearth. She relived each step of her day at the spring, the mewling cries, the feeling of being watched.

She prayed that God would watch over them, keep them safe from harm, and let the Indians know Hester was safe, all right, and in good care.

She thought of her mother, and the need to speak to her rose so strongly in her breast, she felt as if she would suffocate. “Mam. Oh, my Mam,” she whispered, but no one answered. Only the cry of a screech owl reverberated through the surrounding trees, followed by the shrill, undulating reply of his mate.

Instinctively, she reached across Hans’s back, wrapped her arms around his strong body, and felt exhaustion enter her mind. Secure in the sturdy log home, she soon fell asleep. A mouse emerged from the hearthstone and delicately lapped up the spilled cow’s milk before scurrying back into its nest.

CHAPTER 3

KATE WAS PUZZLED WHEN A SUMMER VIRUS PERSISTED. She’d drunk the salted water from the oats she boiled, the way her mother told her. Unable to keep that down, she’d rolled onto her bed in the middle of the day, wave after wave of nausea sending the room spiraling counter-clockwise as she retched into the stoneware chamber pot by her bedside.

Today, she was looking for wild ginger. Hannah Fisher had told her there was nothing better for summer virus than ginger root steeped in boiling water. She combed the north side of the ridge with Hester in a sling on her back, her black hair visible above it, her bright black eyes following every moving object around her.

When Kate was outside, Hester was always quiet, completely immersed in her surroundings, leaving Kate free to go about hoeing the garden, pulling weeds around the cabin, or whatever she chose to do.

It was hot, much too hot to be walking all across the side of the ridge with a baby on her back. Her head pounded, and dizziness set in. She had the evening meal to think about and all the white laundry to retrieve from the fence, fold, and put away.

The heavy summer leaves stirred lazily above her as she sank to her haunches, squatting to take up a corner of her apron and mop her flowing forehead. Her eyes scann

ed the forest floor. May apples, way past their prime, a few mountain laurels, some dandelion, a few ginseng plants, poison oak, but no ginger plant.

She’d go back. Surely, tomorrow the nausea would abate. This was only the summer stomach woes, the way she’d often experienced. She had probably eaten too many onions with the fried rabbit on Sunday evening when Manasses and Lydia had paid them a visit.

The minute she stepped inside the door of the small log house, she knew she had been sloppy and left milk to sour somewhere. She sincerely hoped there were no blowflies on it. Sniffing, the nausea threatening to gag her, she lifted lids, checked the cupboard for spoiling food, but found none. What smelled so sour?

She sniffed Hester’s cradle, lifted the little blanket and pillow and buried her nose in them. But she could not trace the sourness that hung over the interior of her house.

Shrugging her shoulders, she slid her baby off, sniffed her lower dress, then patted her and kissed the top of her head before placing her in the cradle. Immediately, Hester set up a howl of protest, which Kate had learned to ignore, and she soon quieted.

Taking up the poker, she stirred the coals on the hearth, poured water into the iron kettle on its swinging arm, and turned it above the hot coals. She’d boil some beans, adding a bit of salt pork. It was too hot to make a full meal. Hans appreciated cold soup, so she placed raspberries in a crockery bowl, added a dollop of molasses, broke some stale, coarse, brown bread over it, and pushed the bowl to the back of the dry sink. When the beans were finished, she’d add milk to the cold soup, and that would be his supper.

The smell of the molasses brought a fresh wave of nausea, which she stifled by holding her breath. She sank to the wooden settee by the fireplace, surveyed the line of white undergarments and sheets on the fence, and sagged wearily against the wall. She wondered if Hans would offer to bring in the washing.

Surveying the interior of the house, she noticed a few tired-looking cobwebs hanging limply from the ceiling, ashes scattered across the hearth, grease stains on her normally immaculate floors. Perhaps she would die. It had been two weeks, and if anything, the nausea was worse. The house needed a good cleaning, and she had absolutely no energy. It was frightening, suddenly.

There was that sour smell again. Getting up, she began her frantic sniffing, coming up empty-handed, hot, and frustrated. It had to be the hottest summer she could remember.

The beans bubbled in the pot, and she went to the barrel to slice off a bit of salted pork. When she lifted the lid, saliva rushed into her mouth, followed by a hot wetness in the back of her throat. She made a mad, headlong dash for the front door, where Hans found her straining and retching a while later. He put his arm about her waist, led her into the bedroom, and laid her gently on the crackling straw mattress. He said he’d go for the doctor, tonight yet.

No, no, Kate shook her head, desperately not wanting him to spend precious dollars on an unnecessary doctor visit. She assured him she would be fine after she found ginger root and they made tea with it.

Hans lifted Hester from her cradle, cooed and crooned to her, then slid the soft, white undershirt from her shoulders, saying it was too warm to wear anything in this heat. Such a small baby shouldn’t be so uncomfortable.

Hester loved her new freedom, kicking and chortling, blowing little spit bubbles and laughing, while Hans stood and gazed down at her perfect little body, the skin a golden-brown hue. He had tears in his eyes when he told Hester that God had been too good to them. They did not deserve this perfectly beautiful child to have for their own.

Tears formed in Kate’s own eyes, her overwhelming love for him filling her with an almost spiritual emotion. Hans was everything she ever wanted in a husband and father of her children.

It was her friend Lydia Speicher who finally drummed it through Kate’s thick skull. They laughed about the episode for years to come. Kate had gone on her desperate quest for ginger root once more, after a few days of lolling about in the heat, sick, tired, and completely at odds with both Hans and Hester.

Finally, late one afternoon, when it was so hot the whole atmosphere seemed to sizzle, she stumbled on one lone plant. She dug it up as feverishly as a half-crazed man panning for gold nuggets, carried it home, and soon had a cup of the life-saving, fragrant tea.

She took a deep sniff of its fragrance, anticipation stamped on her face, illuminated by the glad light that normally played across her face. But her deep intake of breath turned into a surprised look of disbelief. Before she could swallow, she dashed to the front door and relieved herself of anything she had managed to keep in her stomach.

She would have allowed Hans to bring the doctor, had it not been for Manasses and Lydia’s visit. They lived about seven or eight miles to the east along Irish Creek. They had two children, both boys with curly brown hair and wide-set brown eyes, named Homer and Levi.

Lydia was short and thin, with freckles splattered across her nose, as if God had had an afterthought and sprinkled her face with extra decoration, like a fancy cake. Her hair was mousy brown, her eyes the same color, and her nose was flat and wide. To hold more freckles, she told Kate, wryly.

Manasses was called Manny, for short, and he was of average height, with sun-tanned skin, a shock of brown hair, and eyes that were not really a color, just not white like the area around the irises. He couldn’t grow a decent, manly beard, only a tuft of hair on his chin and a few discolored straggles along the side of his face, which was the source of endless ribbing from Hans.

When they drove their wagon down to the log barn, Hans jumped up eagerly, but Kate dragged herself to the dry sink to begin washing dishes in cold water, fast, before Lydia saw the dried food on them.

It was all she could do to keep from crying when Lydia walked through the door, but she wiped her hands on her apron, shook hands, and said she was glad to see them.

Lydia peered into her face in the fading light of evening and said Kate looked like something the cat had dragged in. In spite of herself, Kate laughed in short, helpless bursts, then told her she’d been sick for many weeks with an upset stomach. She guessed she’d eaten too many onions.

Lydia said nothing, just found the straw broom in the corner and began a thorough sweeping of the hearth. She scrubbed the planks of the tabletop, still saying very little.

Lydia always talked, always, so Kate asked her a bit timidly if she’d done anything to offend her.

“Not other than being dumb.”

“What are you talking about?”

“Katie, you’re …”

Her voice trailed off, as color suffused her face. She blinked, and more color deepened the blush on her cheeks. She stammered. She looked out the window and sighed.

Finally, Kate asked her if she had a serious disease. Was she going to die?

With a tortured expression, Lydia whispered, very soft and low, “You’re in the family way.”

Kate sat back in her chair as if she had received a blow. She blushed as red as the wild strawberries that grew along the bank by the barn. “I can’t be,” she whispered back.

But she was. Hans received Kate’s stammered whispers with whoops and uninhibited yells. They had waited almost ten years for this, and now they would have two. Hester would be a bit over a year old when their baby arrived.

Hans helped her with the garden. He helped her pick the peas and beans and then helped to shell them. He planted carrots and beets, more pumpkins and late onions.

Slowly, the nausea subsided, her energy returned, and she tackled her chores with renewed energy.

They dug the carrots, turnips and beets, carefully placing them in the root cellar behind the house. She helped him make hay, hoe corn, and haul manure.

Hester, barely five months old, sat up by herself now, and Hans made a small wooden box for her. They placed her in one corner and adjusted a feather pillow around her. Everywhere they went, Hester bounced along, her brilliant black eyes shining below the thatch of blue-black hair.

&nb

sp; When the hot sun shone down unmercifully, Hester never whined or whimpered. She sat bolt upright and viewed her world with eyes that missed nothing. Sometimes it seemed as if her skin absorbed every sight and sound and smell, keeping her fulfilled, occupied simply by watching the horses and birds, or smelling the outdoor scents of honeysuckle, ripe manure, and the sun-kissed earth. She loved to sit in the corn rows, playing with the dirt, sifting it through her little brown fingers.

Kate had watched when she’d taken her first mouthful. An angry expression crossed her face, and she let it all dribble back out. What stuck to her tongue, she swallowed dutifully, and she never tried eating it again.

Hans said she was a sensible child. Later in life, he predicted, she would be gifted with many talents, with the amount of things that kept her interested now. Kate agreed, secretly proud of her beautiful daughter. Then Hans brought another small swatch of homespun fabric home, this time a shade of rose, almost identical to the color of the curtains he’d torn down. She swallowed her anger like a bad tincture of herbs, smiled, and said she was pleased.

Dutifully, she produced another fine Sunday dress, placed the little white linen apron over it, and was glad. She asked Hans, though, why he never bought enough fabric so she could have a new shortgown and skirt.

When he became very upset, blaming her for being someone behoft (possessed) with lust of the eyes, she let the matter drop and never brought it up again. She did, however, keep a very small sliver of the fabric and tucked it into the letter she wrote to her mother, asking her if she knew where to purchase something of this shade that was less expensive.

The underarms of her only Sunday shortgown were wearing though, so she patched them, using tiny stitches so no one could tell. It was not unusual to wear the same dress to church for many years. But she felt as if everyone was whispering behind her back about wasting money on the plumage she put on that daughter of hers. Perhaps she was ashamed of Hans’s adoration of Hester. Whatever it was, she wasn’t comfortable carrying her brilliantly dressed daughter into church, knowing her own frock was in a lamentable state.

A Second Chance

A Second Chance Lizzie's Carefree Years

Lizzie's Carefree Years The More the Merrier

The More the Merrier Love in Unlikely Places

Love in Unlikely Places Running Around (and Such)

Running Around (and Such) Wild Horses

Wild Horses Lizzie Searches for Love Trilogy

Lizzie Searches for Love Trilogy Lizzie and Emma

Lizzie and Emma Little Amish Matchmaker

Little Amish Matchmaker The Witnesses

The Witnesses The Healing

The Healing Home Is Where the Heart Is

Home Is Where the Heart Is Fire in the Night

Fire in the Night When Strawberries Bloom

When Strawberries Bloom Little Amish Lizzie

Little Amish Lizzie Which Way Home?

Which Way Home? The Homestead

The Homestead Sadie’s Montana Trilogy

Sadie’s Montana Trilogy Davey's Daughter

Davey's Daughter Hester on the Run

Hester on the Run Disappearances

Disappearances Big Decisions

Big Decisions Becky Meets Her Match

Becky Meets Her Match Hope on the Plains

Hope on the Plains Christmas Visitor

Christmas Visitor