- Home

- Linda Byler

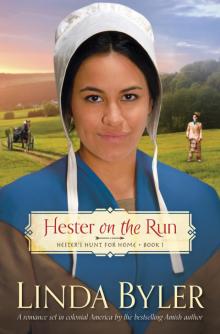

Hester on the Run Page 11

Hester on the Run Read online

Page 11

Hans listened to the children’s tale of adventuresome raspberry picking and fussed over his bedridden wife, his face filled with loving concern. Kate gazed into Hans’s face, his round cheeks gleaming in the light of the fire, and let the love she felt for him hover between them as her eyes stayed on his.

Yes, he was a loving husband, a good provider, a man clever with his tools, building her a bake oven and springhouse, so why would she fret about kindish things like a small bauble he gave to Hester?

Lissie was out at the bake oven wielding the heavy wooden paddle. She removed the piping hot raspberry pies, muttering her grievances to herself, and mumbled her way into the house in time to see the loving exchange between husband and wife. Guilt-ridden, she decided to drop her suspicions then, considering her thoughts nothing but evil surmising, a horrid sin.

Hester tucked the turquoise necklace into the wooden box beneath her bed and felt confident that she had made a friend, a trustworthy one, at that.

CHAPTER 10

KATE’S SHOULDER BECAME SWOLLEN AND streaked with fiery fingers of infection. She lay in bed, miserable and soaked in perspiration as the raging fever tormented her.

Hans brought Dr. Hess. He lanced some of the most infected parts of her shoulder, wrote instructions for the care of it, and left, leaving Hans pacing the floor, his head thrust forward, his hands clasped behind his back.

He was worried about Kate. How could he manage with ten children if something happened to her? Would she be laid to rest beside little Rebecca in the damp earth of that lonely, forsaken graveyard?

He shivered, the shadows around him becoming living things, raking at him with dark, transparent claws.

His breathing became labored. Beads of sweat formed above his lips. He stopped pacing. The suffocating shadows immediately clambered over him with nerve-wracking accuracy. A roaring began in his ears. He stopped the sound with forefingers pushed against them.

Lunging against the door, he fell out onto the pathway in the cool night and lowered himself to a stump in the yard, trembling. He turned, slid to his knees, lifted his hands in prayerful supplication, and begged his God for mercy. “Mein Gott, Mein Heiland!”

Tears rained down his face as he prayed for Kate’s deliverance. When he opened his eyes, the twinkling white of the stars blurred with the silvery leaves that were bathed in moonlight. The lowlying dark barn rose in stark contrast to the surrounding fields. He thought of the growing herd of cows, the pigs. Who would milk them? Who would make butter and cheese? Who would make bacon and sausage?

Kate’s worth rose above him, leaving him reeling with the need to keep his wife alive, and so he prayed on, far into the night until he was completely spent.

The robins set up a raucous chirping before the sun had even begun its ascent over the mountaintop. Hester closed the door of the log house quietly behind her, padding noiselessly on bare feet down to the barn. She stopped to listen to the saucy chirping of the robins, smiled to herself, and moved on. Ambitious birds. They always got the worm first, waking up before anyone else.

“Guten morgen” (Good morning)! Hans greeted her cheerfully. She nodded at her father, a smile parting her lips, as she found his direct gaze.

“Hester, if it’s not too much for you, I guess you’ll have to milk the two cows your mother normally does,” he said, leaning against a rough-hewn post as his eyes surveyed her face.

“How is she?”

“Not good, I’m afraid.”

Hester nodded, alarmed at the pain in her father’s voice. She was spare with words, as well as emotion, so she chose to leave it at that. She reached for the wooden bucket hanging from a nail in the barn, next to the cows’ stalls.

She supposed she could ask Dat if Mam would live, but he didn’t know the answer. No one did. So she became very quiet within herself, sat down on the dirty stool beside Meg, the Brown Swiss cow, and began to milk.

She pulled and squeezed, her strong brown fingers capable of producing jets of warm, creamy milk into the wooden bucket. But by the time the third cow was milked, she wasn’t sure if she could ever open or close her fingers properly again. She rubbed one hand over the other, her face pinched with exhaustion, her mind jumbled with Noah’s inability to milk. And Isaac’s for that matter.

When Hans met her at the barn door, she asked him why she had to milk alone.

“I milked two. Why can’t Noah?”

“He’s too young.”

“He needs to get up early and learn to milk if Mam isn’t well.”

Hans was surprised at Hester being so outspoken, finding it a bit unsettling. Well, the boys weren’t capable like Hester. Besides, he enjoyed the peace and solitude while milking. Hester was quiet and soft-spoken, and those boys would be yakking on about their dumb heita (foolishness), disturbing his morning. He didn’t need them in the barn.

Hester had never cooked breakfast by herself. She came into the kitchen hungry, her fingers dulled by pain, her mother a large form beneath the coverlet, and baby Emma screaming from the cradle. Menno, awakened by the baby’s cries of hunger, let loose with a loud yell of indignation. For a moment, Hester was overwhelmed with inadequacy, a tiny form in the face of a huge, unscalable cliff.

She looked around, her eyes large in her brown face, her dress hanging loosely on her thin frame, tendrils of straight, black hair draped over her forehead and into her eyes.

The house was in disarray. A greasy white tablecloth hung sideways on the plank table, unwashed dishes scattered over it. The redware jar with lilies of the valley that Barbara had picked a fortnight ago was perched precariously on the edge, half full of murky brown water, the small white flowers drooping and half-dead. The floor was strewn with bits of string and corncobs, wooden spools that were empty of thread, colorful pieces of cloth, hay, mud, and dirt.

A rancid odor came from a redware plate in the middle of the table. Hester picked it up and shooed the blowflies from it. Slimy yellow maggots had already hatched from their eggs where the half-cooked rabbit had begun to spoil.

She took the smelly mess to the door, opened it, stepped out and away from the house, and flung the spoiled food angrily into a briar patch. Let the vultures find it.

She stood very still, lifting her eyes to the rising sun. She let her gaze wander across the beautiful green ridges that fell away on each side of her, over the sturdy, gray, log house, and the barn below it, the stone springhouse, split-rail fences, the lush pasture with grazing cows behind it. The sky was lavender, the rosy-hued sunrise turning into a heavenly color.

She turned to the sun, the yellow orb warm on her skin. The Creator made the sun, the land, and her. She felt a part of the waving grass at her feet, the moving leaves over her head. She was here. This was her home. She couldn’t separate herself from the forest or the sky or the sun. God had made it all, set her here with this family. They were hers.

Taking a deep breath, she lifted her face to the sun, letting the pores of her skin absorb its warmth, receiving its strength. The rustling of the leaves from the great oak tree whispered its resilience against drought and storms and hordes of insects. The morning breeze lifted loose strands of her hair, caressing her smooth brown forehead, and she felt the breath of her Creator. She would be strong. She would do her best. In the face of all the obstacles, she would be able.

In the house, she changed the baby’s cloth diaper, swaddled her in a warm blanket, and then set Isaac to work feeding her. In clipped words, she ordered Noah down to the barn, telling him he should have been down there since five when she went. He cast her a red-faced look of shame, but she already had her back turned, retrieving the heavy, cast iron pot from its hook.

She wrinkled her nose at the residue of burnt beans, then carried the pot outside and sloshed tepid water into it from the bucket on the bench beside the door. Better let that soak. She’d watched Mam soak burned beans.

Daniel and John were awake and already quarreling, their long nightshirts stained from too many

nights of being worn and too few washings. Their hair was stiff and tangled, their eyes heavy with sleep and the inability to understand.

“Solomon, get the boys’ knee breeches,” Hester called, from her station by the fireplace.

“Where’s Mam?” he asked.

“Asleep.”

“Why?”

“She’s sick.”

Climbing to the top cupboard on a kitchen chair, Hester got down her mother’s recipe from the pile she kept there, then snorted, a balled up fist on each hip when she realized she could not read the recipe. Well, she’d watched Mam.

Taking up the clean, cast iron pot, she filled it half full of water, added a handful of salt, hung it on the heavy, black hook, and swung it over the fire. Grabbing the heavy poker, she stirred up the coals and barked a command to Isaac, who laid the baby in her cradle, where immediately she set up an awful howling. Unsure what to do, Isaac hesitated but was immediately pressed to a choice by Hester’s second set of orders. She wanted wood for the fire. She wanted it now.

He dumped the wood on the glowing ashes, which sent up a shower of sparks. But Hester chose to ignore that as she sliced bread on the dry sink.

She put Lissie to work cleaning the dirty dishes from the soiled tablecloth, telling her to shake the cloth, replace it with a clean one, and set the table with clean, redware plates. She put down redware cups and a spoon with each plate, then placed a pat of butter on a small plate in the middle. The breakfast table was set.

Hester stopped, hearing her mother’s soft cries. Swiftly, she went to her and bent low, listening. Her anxious wails were punctuated by hiccups, her ramblings unintelligible. Hester placed a hand on Kate’s forehead, then drew back, catching her lower lip in her teeth, surprised by a sharp intake of breath.

Her mother would die. Already her festering wounds were odorous.

Hester ran with the speed of the wind, breaking into the cow stable where she found Dat, who looked up, surprised.

“You must come. Mam is very … she’s burning hot.”

With an exclamation of dismay, Hans let the pitchfork in his hands fall to the floor with a dull thud. He followed Hester from the barn, then flung himself by his wife’s bedside, groans of despair wobbling from his loose, heavy lips.

“The doctor. The doctor!”

Hester looked at her father sharply. It was not proper for a girl to ride, but she had no choice. Her mother would die.

Lifting agonized eyes, Hans said, “Noah. Go.”

Noah, terrified, shook his head. “I don’t know the way.”

“You have to go.”

Hans was wailing, his teeth bared, as his lips drew back in unaccustomed fear.

Hester mulled the way in her mind, the forks in the path, the ford across the river. Already her heart pounded, knowing she would be the one to go. Hans couldn’t. His beloved Kate might die in his absence.

She pulled on a pair of Noah’s patched knee breeches, whistled for Rudy, the blue roan, caught him easily, and slipped the halter on his head and the bridle with the smallest bit attached to it. Then she stood aside, grasped a handful of the coarse mane, and flung herself up onto his back.

Rudy lifted his head, wheeled, and was out of the barnyard through the gap in the rail fence and onto the road that led to the doctor’s house in Irish Creek.

Dust rose in little puffs as Rudy’s hooves thundered down the grass-covered road. Deep ruts were cut into the road where spring thunderstorms had poured buckets of rain on the hilly landscape, sending gushes of muddy water down every incline. Rudy was surefooted, but Hester kept a watchful eye for especially deep and treacherous grooves, ducking her head, her face against the flying mane whenever a low branch loomed ahead of her.

The first fork in the road was a surprise, but she knew enough to stay left, and they thundered on. A small branch, like a whip, caught her forehead. She felt the sharp sting but let it go. When she put her hand up, her fingers came away sticky with blood that seeped from the wound.

The trees were thinning now, just as the road turned to the left yet again. When it headed steadily downhill, she knew they were close to the river. She remembered the boatman at the ford the last time she’d come to the trading post with her father.

When the road leveled off and Rudy’s hooves sank deeper into the sandy soil, she caught a glimpse of the sparkling water, sunlight glinting from its wavelets, the water dark green, gray, and brown all at the same time.

She pulled back steadily on the reins, her dark eyes peering ahead into the unknown, a troubling scene that was the river and its ford, a large raft, a rope, and a boatman with a long wooden pole. A woman alone was never good, and she was only a girl. She’d heard Hans speak to Kate about this ford and the questionable characters that regularly took too much money from honest travelers, or worse.

She had no time to decide her plan or the action she would take if the boatman was dishonest. She had no money. She had forgotten the coins she’d need, overcome as she was by wanting to save her mother.

At a trot now, Rudy broke through the line of trees, Hester low on his back, her eyes downcast. She had seen the boatman and was fully aware of his flaming red hair, his youth. She could only try.

She pulled Rudy to a stop. His nostrils quivered, his sides heaved, sweat stained his odd, bluish-gray, cream-colored flank.

The youth was tall, thin, and dressed in a clean linen shirt and knee breeches. His feet were brown and bare. His face was dark-skinned, his freckles barely visible, his eyes green. His head looked as if it was on fire, his hair was so red.

He looked up, said, “Har.”

Hester said nothing. She sat still as a stone, her black eyes watching his green ones.

It gave him the creeps, so he said, “Har,” once more.

She nodded her head, then continued to stare.

He jerked his thumb in the general direction of the river.

“You want across?”

“Yes.”

“Five cents.”

“I don’t have money.”

“Then yer gonna haf to swim.” Rudy snorted, turned his head at the small tug from Hester’s hand, and started down the embankment to the waving grasses at the water’s edge.

“Hey! I didn’t mean it.”

“Say what you mean.”

The youth watched as she turned her horse again, then slid off with the ease of long practice. She was just a slip of a thing. Couldn’t be older than fourteen. Maybe even thirteen.

“You shouldn’t be by yerself.”

“My mother is very sick. I’m going for the doctor.”

The youth whistled. “That’s a long way off.”

“So.”

“Why don’t you go to Trader Joe’s? Indians all over the place.”

“I’m not going for an Indian.”

“Why not?”

“I want Doctor Hess.”

“You’re an Indian, ain’t you?”

“I’m an Amish Indian.”

“A who?”

“Take me across.”

“S’ wrong with yer ma?”

“She’s … She was … She has wounds. They’re festering. She has a fever.”

“You don’t need a doctor. You need Uhma. She’s a herb healer. Sort of like a witch.”

Hester looked at him, wide-eyed, her face revealing nothing.

“Did you already have the doctor?”

Hester nodded.

“I figured.”

The youth stood looking across the water, then turned and looked back the way she had come. He seemed to be considering something. He looked at Hester finally.

“Look. Is your ma dying?”

Hester shrugged her shoulders, her eyes flat, giving away nothing.

“Can you stay here and let me take your horse?”

“No!” The sound was an angry outburst, a vehement refusal.

“Then you’re going to have to let me up on your horse’s back. I can’t give you directions.

I have to take you to Uhma’s house.”

“Your mother?”

That question showed the crack in her steely resolve, and he said quickly, “No. Everyone calls her Uhma. She’s an old, old Indian woman that mixes herbs and stuff. If your ma was bit and has a fever, ain’t much Doc Hess is gonna do, trust me.”

He watched the young girl’s face. Nothing changed in it. Her eyes didn’t blink or her lips part or anything at all. Her answer was merely a dipping of her head, the glossy black hair visible instead of her face. Was she Indian or wasn’t she? She sure was pretty, he thought, but odder than a two-headed calf.

“Come,” she said, suddenly.

In one swift movement, quicker than he had ever seen anyone mount a horse, she swung up on her horse’s back, looking down at him. He met her black eyes, a question in his, and she nodded. He had to grab a handful of the horse’s mane, but she sat firm as he flung himself up, his left arm raking across her middle.

He pointed to the narrow trail following the river, and she goaded Rudy into action, his hooves pounding the wet sandy earth with dull thunks as they sped along the river bottom, skirting willow trees, honeysuckle vines, and great arches of raspberry and blackberry bushes hanging across the trail.

Blue jays screamed their hoarse cries as they flew out of their way. Fat groundhogs sat up, listening, then lowered themselves and waddled out of sight at their approach. Turtles sunning themselves on half-submerged logs slid silently into brackish water, and frogs briefly stopped their endless croaking, starting back up again after they passed.

The road led up from the river bottom into dense forests of pines and briars so thick, the road became only a trail. Jagged rocks protruded from the pine needles, and the pines thinned to a few dead, old trees, charred from some long-ago forest fire. Seedlings sprang up everywhere, the sunlight filtered through the dead trees giving them life.

The trail became steeper with rocks jutting out over it. Hester slowed Rudy, afraid of the sharp edges. She lifted her head. She heard water. She remained silent, thinking the youth would speak if she needed to know something.

A Second Chance

A Second Chance Lizzie's Carefree Years

Lizzie's Carefree Years The More the Merrier

The More the Merrier Love in Unlikely Places

Love in Unlikely Places Running Around (and Such)

Running Around (and Such) Wild Horses

Wild Horses Lizzie Searches for Love Trilogy

Lizzie Searches for Love Trilogy Lizzie and Emma

Lizzie and Emma Little Amish Matchmaker

Little Amish Matchmaker The Witnesses

The Witnesses The Healing

The Healing Home Is Where the Heart Is

Home Is Where the Heart Is Fire in the Night

Fire in the Night When Strawberries Bloom

When Strawberries Bloom Little Amish Lizzie

Little Amish Lizzie Which Way Home?

Which Way Home? The Homestead

The Homestead Sadie’s Montana Trilogy

Sadie’s Montana Trilogy Davey's Daughter

Davey's Daughter Hester on the Run

Hester on the Run Disappearances

Disappearances Big Decisions

Big Decisions Becky Meets Her Match

Becky Meets Her Match Hope on the Plains

Hope on the Plains Christmas Visitor

Christmas Visitor